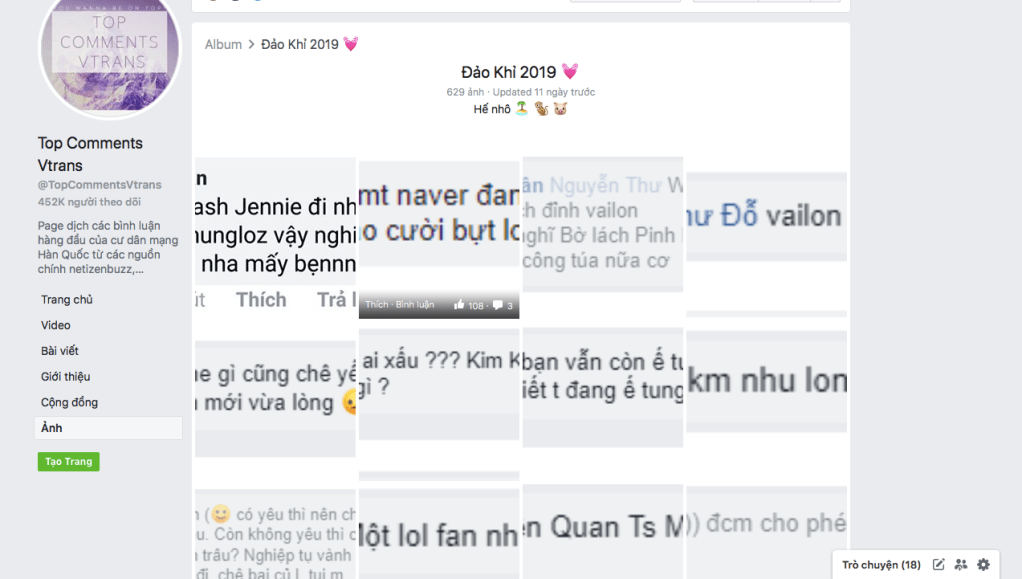

In my independent autoethnography, I maintained two tangled field sites to investigate my recent media consumption of reading translated Chinese netizens’ top comments. While Facebook functioned as my “contextual” field for a bounded online community, Twitter became my “meta-field”, which aggregates scattered communicative contents (Airoldi 2018, p. 662).

Review the Scope of the Project

Despite the distinction between the two, they complicated my research process. I needed to switch back and forth between Facebook and Twitter, which is time-consuming and inefficient due to changes in the meta-field site. As screening sessions ended in week 6, discussions about Asian films quickly die off. This situation led to the lack of cultural outsiders and insiders’ input for me to further examine the potential of paratexts in replacing central texts to broaden cultural knowledge of a wider public.

The irrelevance of the meta-field site made me realize that the scope of my autoethnography was quite narrow, considering that it was a trial account. To expand on my autoethnographic experience, I decided to focus solely on Facebook – my contextual field site – for studying the production and consumption of paratexts, in which translated comments surround not only Chinese films but also other texts, such as music or social issues. I also reconsidered my choice of Facebook page to find a cyberplace that delivers a variety of translated comments on different media products and topics.

The Problem(s) of Cultural Interpretations

As I am interested in the Chinese entertainment industry, I read online translated Chinese top comments, as well as entertainment news, from Zhihu and Weibo on Facebook to gain insights into the Sinophone sphere. My habit appears to be bizarre since there are many ways to explore a culture. Popular options, such as traveling, learning foreign languages, and direct media consumption, which offer cultural outsiders first-hand knowledge of a particular culture.

Conversely, reading translated comments provides readers with second-hand cultural understanding (Mansour & Francke 2017). Translated comments undergo interpretation twice, including the interpretation of the Chinese-based audience and the interpretation of the translator. Such a double information filtering process often risks distorting the original messages (Thomas & Round 2016, p. 243), and indeed, distortion frequently happens.

“As top comments receive much conformity and agreement, Vietnamese readers understand them as the public sentiment of South Korean or Chinese people”.

In my interview with a former K-pop fan page administrator and now a regular reader of both C-nets’ and K-nets’ comments, she said that the credibility of top comments is only valid within the social community. That being said, top comments translated from Zhihu only represent opinions of Zhihu users instead of other platforms like Weibo or the whole Sinophone sphere. I also notice that Vietnamese Internet users usually bear in mind the notion that the massive number of likes on a thread of a social media platform in China, compared to the votes up on Korean or Vietnamese topics, means the attitude of the majority of the Chinese population.

Furthermore, cultural outsiders often adopt an ethnocentric standpoint in understanding a different culture, imposing their existing knowledge of their countries on another (Dwyer 2013, p. 133) . In this case, many Vietnamese netizens fail to take into consideration the demographic differences between the two countries. A thousand likes may mean much for a top comment on a Vietnamese topic on Facebook, yet that number of likes is far to make the top on Weibo. Indeed, Weibo top comments often receive a few thousand to around twenty thousand likes and shares, depending on how heated the topic discussions are. The interpretation of a number of Chinese netizens should not be viewed as the whole society’s opinion on a particular matter.

The frequency of the social media platforms chosen to be translated is another and an intertwined reason for Vietnamese readers’ mistaken notion of top comments as Chinese public sentiment. The more they see topics on a particular platform being translated, the stronger their false belief that the platform is popular amongst cultural insiders.

The frequency of a source or topic translation has more to do with the decision-making of the translator in selecting information selection rather than the platform/ portal or the thread themselves. For example, Nate and Pann are negative news portals, in which the top comments are filled with hate and adverse reactions towards celebrities in Korea. Although many top comment V-translation pages usually translate threads on these portals, Nate and Pann only account for 2% of Internet users in South Korea (Cruz et al. 2019, p. 12).

Benefits of Reading Translated Comments

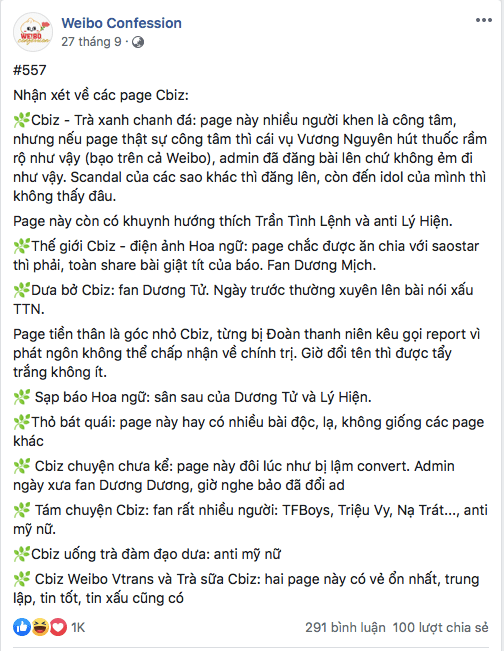

Regarding translated Chinese top comments pages, readers seem to be less skeptical about translators’ biases in the translation process than translated Korean comments pages. As these pages claim to be “public pages” rather than fan pages like translated Korean comments pages, they try to offer a broader range of news about many Chinese artists and their works, which include both the popular and the unpopular. Such a variety of information makes Vietnamese readers believe in the objectivity and balance of the translated threads and top comments.

However, the bias mechanism of information selection of moderators of C-biz news lies in bringing negative content instead of using negatively emotive language for translation like K-pop comment pages. Drawing on my personal experience of following many (if not all of the mentioned) C-biz comment translation pages on Facebook, I must agree with the below confession about the tendency and nature of these pages in translating top comments. Overall, the second layer of page moderators’ interpretation exacerbates the dissemination of misinformation, leading to the decreasing value of second-hand knowledge.

Paratexts: Shifting the Peripheral Boundary

Despite these problems, reading translated comments in particular and second-hand knowledge in general are appealed to me and many other people. Shared the same reason with the interview, my friend admitted that she treats those comments as news. Since both of us are more interested in the impacts of information and its implications of communication rather than the data and the artists themselves, the translated comments shift from paratexts to central object for my cultural studies.

I treat translated comments and paratexts as the news itself instead of news accessories. I find reading translated comments helpful in creating “reading formation”, which allows me to read between the lines and understand the underlying cultural concepts of the Chinese context. For example, if there is a rumor about a sponsorship or advertisement a Chinese celebrity gets, the rumor is 90% true (Lebold 2011, p. 1030).

“Reading formation refers to the intertextual relations which prevail in a particular context, thereby activating a given body of texts by ordering the relations between them in a specific way such that their reading is always-already cued in specific directions from such relations”

Bennett and Woollacoot 1987.

Furthermore, reading those comments means actively throw myself and my friend into random political-social debates, stimulating our critical thinking and problem-solving processes. Surrounded by like-minded people at university, I often feel the need to reach out more to dissident voices. While Facebook is criticised for “filter bubbles”, turning users’ newsfeed into echo-chambers (Marchi 2012, p. 256), I find translated top comment pages on the platform as a public sphere to discuss and educate myself on different matters of life. Although these pages are not totally Habermas’s (1990) “ideal speech situation”, I still enjoy my exposure to different opinions to enhance my media literacy in such a post-truth environment.

Translated Top Comments Threads as a Community?

Translated comments serve as a valuable cultural tool in assessing transnational cultural relationships, considering that those comments originate from the cognitive authority – the cultural insiders (Pjesivac et al. 2018, p. 23). Therefore, second-hand knowledge becomes credible and useful to rely on decoding cultural elements. From the translated comments, I could understand the translation practices of transnational fandom. Translated top comments pages are simply another type of fan pages for idols and favourite artists.

Similar to the case of my interviewee, most moderators of fan pages are “executive fans” promoted to managers of the sites (Thomas & Round 2016, 241). Despite their attempts to stay objective in translating topics, they often skew the readers’ opinions and utilise their administration power to filter and ban dissident voices. Accidentally, moderators build an “imagined community” (Anderson 1983), in which people must adhere to the collective “rules of game” set by the owners of that cyber place (Chan 2017, p. 43). This somehow leads to the “spiral of silence”, which deters different voices to be heard. Thus, to stay in the “community”, I remain silent online and discuss issues with my friends offline to freely express my ideas.

“Imagined communities” are whose members believe in a sense of comradeship despite possibly not knowing every single one of each other”

Anderson 1983

(You can find the audio of my interview and the script in the References page)